Earlier this year, I calculated average salary estimates for the public and private sectors in Ireland. The answer, that the average worker in the private sector earned €40,000 last year, almost €10,000 less than their public sector counterpart, has proved if not controversial than certainly a starting point for debate. Given some of the comments on that blog post, and the fact that the teachers conferences were being held last week, I decided to look in a little more depth at the education sector. How much do teachers in Ireland earn? How does this compare with other people in Ireland? How do teachers’ salaries in Ireland compare with other eurozone teachers?

Trade unions have been clear on one point since the size of Ireland’s fiscal crisis became clear: those most in a position to pay should bear the brunt. At the same time, teachers unions have said that their pay is not up for discussion. This implies that teachers presume that they are not among those most in a position to pay. How does that stack up with the stats? The chart below shows average earnings in mid-2007, the latest data across all sectors, with public sectors marked in dark blue, private sectors in light blue, and semi-state in mixed blue.

The single most striking thing is that all the best paid sectors in Ireland are either public or semi-state industries. (Those looking for more detail might start with Dept of Education figures out last week showing that primary school teachers earn on average €57,000.) Surely, any objective trade union leader should be arguing that whatever burden workers have to bear, the bulk of it should be borne primarily by the public and semi-state sectors.

There are a few common queries people have with the relevance of these statistics. The first often runs: “Hang on, you’re not comparing like with like. All teachers have a degree, while who knows how many people do in, say, paper and printing.” Ideally, I’d like to have the stats to hand to explore this. Unfortunately I don’t. My only comment before we move on is that if finance and business services had come out as the best paid sectors in Ireland, would the same people have argued that we should wait and see whether their higher wages were justified by qualifications/experience/profit created? Or would people have argued that as they were best paid, they should pay most?

Let’s move on, though. If comparing education with other sectors in Ireland is not fair, let’s compare Irish teachers with their eurozone counterparts? After all, our old trick in situations like this was just to devalue and hope for the best. Now we share a currency with a dozen or so other countries. Are our teachers overpriced?

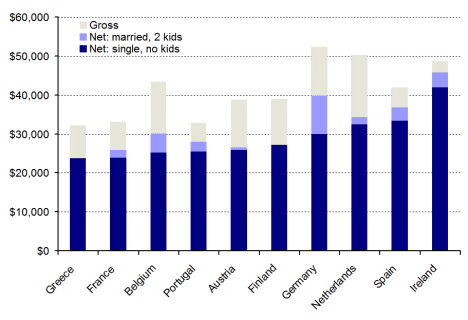

The graph below uses OECD statistics to examine teachers’ salaries across the eurozone. (I’ll take this chance to recommend the OECD’s Education at a Glance 2008: even if you hate absolutely everything I’m saying here, do take the opportunity to wander around its facts and figures.) In Ireland, a teacher in the job 15 years, single with no kids, earns more after tax than his or her counterparts do BEFORE they’ve been taxed in most other eurozone members. Marry that teacher off and give them two kids and – despite Germany’s best efforts to catch up – Irish teachers are by far the best paid of the ten eurozone countries shown.

OK, so Irish teachers are well paid relative to other Irish workers – they may just be better qualified. And yes, they’re paid substantially more than their eurozone counterparts. Perhaps price levels are so substantially higher in the rip-off republic that teachers in Ireland need this extra pay just to break even? Unfortunately, eurostat figures on comparative price levels don’t back that assertion up. Whereas prices in Ireland are indeed 15% higher than in France, the single teacher above enjoys 75% more take-home pay. In Finland, prices are just 2% below Irish prices, but an Irish teacher enjoys a wage that is 54% higher than a Finnish counterpart.

If prices don’t explain the international gap, maybe Irish teachers work a longer year than their eurozone counterparts, explaining why they get paid more. Unfortunately again for Irish teachers, the opposite seems to be the case, as the graph below shows. Teachers – particularly secondary school teachers – work less days on average than almost all their eurozone counterparts. This leaves the amount paid for every day spent teaching in Ireland looking pretty unsustainable. Factoring in the pension levy only scratches at the surface of the problem.

Ireland is currently grappling with a huge fiscal and economic crisis. The government faces lots of tough choices about what stays and what must go. The fact that they’ve chosen to cut back some education services suggests that they are missing what should be obvious: the more we bring Irish teachers’ salaries back in line with counterparts elsewhere in the eurozone, as well as with other sectors in Ireland, the less we’ll have to cut back on the range of education services we offer.

As teachers of maths should appreciate, the arithmetic is simple. The government needs to make savings across the board in publicly-funded services, including education. To make savings in education, we can either cut back on education services (quantity) or cut back on teachers salaries (price). Teachers have so far been successful in passing those two issues off as one, and thus creating a somewhat bizarre alliance of service providers (teachers) and consumers (parents/children).

Given how Irish teachers’ pay compares domestically and internationally, it’s time we separated out teachers’ pay from education cutbacks and took a long cold look at what our teachers are paid.

Filed under: 1 Irish Economy | Tagged: 1 Irish Economy, education, education cutbacks, eurozone, ictu, ireland, irish trade unions, public sector, public sector earnings, public sector pay, recession, teachers earnings, trade unions |

[…] says yes and judging from his last graph, by quite some distance even including the pension levy: Tackling the thorny issue of teachers pay Ronan Lyons | Blog I think his earlier post on average salaries in public and private sectors may have been linked […]

[…] comparisons within Ireland aren’t good enough for you, how about cross-country comparisons? Tackling the thorny issue of teachers pay Ronan Lyons | Blog Teachers in Ireland are paid about twice as much per day teaching as teachers in many other […]

The mood in Mary Immaculate College, Limerick has echoed the mood the of the country in recent months. As I can only assume that the situation is similar in the other teaching colleges in Ireland. And with good reason. Next September these colleges are sending over 2.000 newly qualified teachers into a jobs market that bears a close resemblance to the Gobi desert. Any hope of finding a job for September, permanent, temporary or otherwise has been extinguished by a minister more concerned with stop-gap solutions than long-term goals. And for the remaining students in these colleges, the approaching threat of college fees being sadistically dumped on top of registration fees & accommodation costs hardly help morale.

Apologies for the woe-is-me speech, but these facts are undeniable. This makes it much more difficult to agree with comments made recently in the national media that teachers should “Stop whinging and do the job”. Anyone who can claim that teaching is a soft or cushy job clearly did not pay enough attention in school. A teachers working day does not end at three o’clock. To maintain the standards of education that this country requires & which are, quite rightly, expected by parents, hours of preparation are required. This is not including the vast amount of time the average teacher voluntarily gives up to coach the school team, conduct the choir, run the homework club, etc. Irish teachers are more highly paid than the average European counterpart, but with good reason.

The argument being made that teachers are using children as an excuse not to take a pay cut is ridiculous. Anyone who tells you that the raising of class sizes (already one of the largest in Europe) or the cutting of Language support teachers will not be harmful to children’s education has obviously never set foot in a classroom. Leaving aside all other factors, children will suffer because of these measures. And to argue that teachers should stop complaining, because they have a secure job with a good pension. I will happily point you in the direction of anyone of the 2,000 plus newly qualified teachers who will be joining dole queues shortly, or the hundreds of teachers who will be behind them in the queue in September when class sizes are lowered and they lose their “secure” jobs.

While your facts about teachers pay in Ireland being considerably higher than European counterparts are true. You have forgotten to mention the Irish Education system is ranked as one of the best in the world, yet it is ranked as one of the lowest-funded education systems in the world. It also has one of the largest average class-sizes in Europe. I have, as part of my training, had the opportunity to teach abroad. It is much easier to teach a class of 15 (belgium) than 36 (Co. Clare).

In conclusion, the teachers of this country are not “whinging” but standing up for both themselves and their pupils. Any teacher with an ounce of experience that teaching has not gotten any easier over the years. There have been marked increases in disruptive behaviour in classrooms, abusive parents & job security is most certainly not universal in the profession. To do our bit for the economy and the country, our jobs are being made more difficult, and we are being asked to accept this challenge for less pay. More importantly, children will suffer.

Hi Rory,

Thanks for stopping by and taking the time to comment. I guess what I was hoping to separate out with this post was some of the issues you raise in your comment.

“Anyone who tells you that the raising of class sizes (already one of the largest in Europe) or the cutting of Language support teachers will not be harmful to children’s education has obviously never set foot in a classroom.”

I agree that service shouldn’t be cut if at all possible. But where we disagree is that I believe we essentially have an either/or here, because our public monies are very limited. We can *either* cut teachers wages *or* raise class sizes/cut language support, etc. Given the evidence I found on teachers wages, I know which I’d do!

One other question for Rory:

Do you honestly believe that Irish teachers work 80% harder than their Portuguese counterparts and 50% harder than their French and Finnish colleagues?

I’m not a teacher of maths, but this strikes me as a disingenuous presentation of the data. Let’s take only one example. You claim that Irish teachers make wildly higher salaries per day than their European counterparts. The OECD study that you’re citing, however, refers mostly to pay per teaching hour and for what should be obvious reasons: if Ireland has a longer school day that could well more than compensate for a shorter school year. On page 453 of the OECD Education at a Glance 2008 report, If you look at the columns labelled ‘Salary per hours of net contact (teaching) time after 15 years of experience’, you’ll find three sets of numbers, for primary, lower secondary and upper secondary education. In Germany, the numbers are 62, 68, 78. In Ireland the numbers are 53, 66, 66. The EU19 averages are 48, 61, 72 and the OECD averages are 46, 58, 68.

So if what we’re measuring is pay per contact hour, Irish teachers make less than German teachers, not more. If you were measuring pay per student contact hour, given Irish class sizes, I’m sure Irish teachers make even less than German ones. And this is not negligible: more students means much more work outside of class.

Sure, Ireland is above the EU hourly averages for primary and lower secondary teachers and below them for upper secondary teachers. But it isn’t wildly out of line as your post would lead your avid readers in the Independent media group to believe.

I can only wonder why you would seek to present such misleading statistics. But let’s be clear who the vested interests are that give such misdirection a much wider echo than it deserves: they are Fianna Fail politicians who want to scapegoat the public sector as a way of distracting from their total mismanagement of tax policy over the boom years. And they are IBEC and the business lobby, who want to make sure, above all, that their taxes are not increased. So they hammer the public sector despite clear evidence that Ireland’s public sector expenditure is not out of line with international norms and did in fact decrease relative to both GDP and GNI over the boom years.

I’m surprised and chagrined that you have agreed to be their accomplice in this.

I understand where you are coming from, but what I’m trying to impress is that before the economic crisis came to the forefront of media attention, classrooms in Ireland were already more difficult teaching environments than the average European classroom. I am completely in favour of teachers “doing their bit” to help the financial problems in the country, just like every other profession. However, while several other public service professions will also see a reduced rate of pay in the next few years, teachers will experience this reduction and have their work load increased dramatically.

Perhaps this would not be such a bitter pill for teachers to swallow if not for the fact that during the boom years we saw drastic mismanagement of the education system by the government. To give one example, the vast majority of primary schools in this country have at the very least one prefab. I have been in schools which are aproximately 75% prefabs. Prefabs were introduced as a temporary solution, and for some reason have become a permanent fixture in schools. In many cases the government is paying up to €100,000 annually to rent ONE prefab. It is difficult to stomach this mismanagement of finances & resources for years, and then be asked to take a substanial pay cut.

And I would not claim to work 80% harder than anyone. But I could make the argument that if I have 50% more students, then I that 50% more work for me to do. (Not that I mind)

re: people with a degree in non-teaching areas. Why would you not include apprenticeships in this? Serving 4 years of practical based training (in particular if the job is practical in nature) surely hones the persons skills to a high level required for that job.

If you are doing a particular type of work the training needs to be specific to the job at hand, teaching by its nature is education based and therefore having a degree is the foundation requirement, on the other hand a pro-boxer with a degree won’t be able to utilise that training in order to pursue their profession.

Odd example, but the point is simple, training is relevant to the task at hand

An anonymous comment from a friend of a friend, who is a teacher:

“Average is skewed by the massive amounts principles are paid…believe me I get nothing near that! My principle is paid top money for actually doing bugger all as our incredible secretary really runs our school. I’d like to see less automatic appointments and more assessments of staff.

I have to spend an average of 8k a year of my own money making up the shortfall, for example I have to pay the heating for my after school activities myself as the school can’t afford it. I also pay the insurance necessary, and rent the buildings for my remedial classes. I don’t get paid for any of that, so my hours worked aren’t taken into account in those figures. Thats before the costs of the extra materials I buy, the lunches I provide, the breakfast club I personally fund…. I’m not the only one in this position, and I doubt that many of the older teachers who joined for the hours and the holidays are among us.

Generally, all told, I average a 10.5 hour day. With just a half hour offical break, which is purely theoretical in the general run of the day. However, I love my job, and couldn’t do anything else.”

My own comment in response:

I’m delighted to see a teacher on the ground bring up the topic of reward/incentive/pay structures. I couldn’t agree more – reward teachers who work hard, and Ireland will reap the rewards.

Hi Ernie,

Thanks for taking the time to read and comment in detail. Hopefully, I can do justice in my response:

“The OECD study you’re citing refers mostly to pay per teaching hour and for what should be obvious reasons: if Ireland has a longer school day that could well more than compensate for a shorter school year.”

While you have a point, the two are not independent. 200 hours a year could translate into 10 hours a day for 20 weeks, or 5 hours a day for 40 weeks. The latter gives teachers greater time to prepare, assess, stay up to date on their subjects, engage in training, etc. It would also give them greater time to be assessed on an ongoing basis – crucial to long-term sustainable wages that reward hard-working teachers.

“So if what we’re measuring is pay per contact hour, Irish teachers make less than German teachers, not more.”

Arguing that Irish teachers are paid less than one other country by one measure is not the same as arguing Irish teachers are not overpaid/are underpaid.

“But it isn’t wildly out of line as your post would lead your avid readers in the Independent media group to believe.”

Do I have readers in the Independent group? Is someone syndicating my blog without my knowing?! (No, really – I don’t get this reference!)

“I can only wonder why you would seek to present such misleading statistics.”

You mightn’t like my results, you may be able to argue on the margins somewhat (Ireland is 2nd most expensive, not most expensive, etc.) but hopefully you don’t honestly think I’m trying to be misleading… do you?

“But let’s be clear who the vested interests are that give such misdirection a much wider echo than it deserves: they are Fianna Fail politicians who want to scapegoat the public sector as a way of distracting from their total mismanagement of tax policy over the boom years.”

OK, I don’t know how we got there, but we 100% agree! The last 10 years of government have been disaster in terms of managing the public finances.

“And they are IBEC and the business lobby, who want to make sure, above all, that their taxes are not increased.”

It’s my belief that taxes should and will go up. But expenditure should and hopefully will come down too.

“So they hammer the public sector despite clear evidence that Ireland’s public sector expenditure is not out of line with international norms and did in fact decrease relative to both GDP and GNI over the boom years.”

It’s not just about total levels of expenditure – it’s about how it’s spent. If we spent less on teachers’ core salaries (say $150 per teaching day), we could spend more on bonuses for good teaching, more on teacher training, more on computers and new schools, more on extra teachers for remedial/language support, etc. And still save money.

(Apologies for the length of my reply.)

[…] and education up 5%. Utilities and local charges up 11%. And the original figures cited here, Tackling the thorny issue of teachers pay Ronan Lyons | Blog, did indeed compare purchasing power costs. Prices are similar in Ireland and Finland, but teachers […]

You wrote:

“Arguing that Irish teachers are paid less than one other country by one measure is not the same as arguing Irish teachers are not overpaid/are underpaid.”

Germany is only an example. According to the misleading chart you put up, Irish teachers made something like 150% of their German counterparts per diem. I’ve now pointed out the ways in which that statistic is misleading based on the very study you’ve cited (but I notice you give no references for where you got the figures used in your charts). It is misleading because pay per diem is not a relevant metric. Pay per contact hour is more relevant but still not as relevant as pay per *student hour*.

Now, as I pointed out (Germany was not the only country referred to), Irish teacher pay per contact hour is slightly above the OECD average for two categories of teachers (primary and lower secondary) and slightly below for one category (upper secondary) for teachers with 15 years of experience. But nothing in your blog post would lead anyone to have any sense of this: rather, your blog post would lead them to believe–based on evidence that you haven’t presented–that Irish teachers are wildly overpaid. So, I don’t know whether to think that you’re intentionally being misleading. But you are being misleading, whether intentionally or not.

If you look at the chart on p. 424 of the report, you’ll find that Ireland has the largest primary class sizes in Europe (assuming Turkey is not part of Europe) and is well above the OECD average for class sizes at all levels. The OECD report doesn’t give the information that would allow us to work out pay per student contact hour, but given the large class sizes and the impact large classes have on workloads outside of contact hours, I’m willing to bet that Irish teachers are rather a bargain by this metric.

And that’s the important point that you and your admirers (Brendan O’Connor cites your blog) never seem to get: Ireland made a political choice to have fewer teachers teaching larger classes for long hours and getting paid accordingly. Critics only want to point to the salary levels and want to wave away the other aspect: large class sizes and relatively high contact hours. But to do that is to distort the issue by means of statistics. You don’t seem like the kind of guy who is wont to engage in such distortion deliberately. But that little graph with the per diem rates of teachers that you derived from who-knows-where is the sort of distortion propagandists pay good money to produce. And I expect to see it picked up and turned into a dishonest headline (Irish Teachers By Far Best Paid in Europe!) in the Irish Independent in the coming days.

Finally, with regard to the last paragraph of your reply: does anyone believe for one minute that the lobby in favour of cutting teacher pay is planning to use the proceeds to fund other aspects of the educational system? Frankly, I hadn’t noticed that the pensions levy was being earmarked to rid the country of prefabs and build permanent schools. In short: that argument is a complete red herring and you know it.

Hi Ernie,

Thanks again for the comment. All my figures are taken from the OECD, from the Education at a Glance figures (Chapters B and D) and from their Taxation database (Table I.3). Full details available on request – very few people ever seem interested in my stats, though 😦

While you are commenting on my blog, you seem to fighting a different demon other than myself. You say, “does anyone believe for one minute that the lobby in favour of cutting teacher pay is planning to use the proceeds to fund other aspects of the educational system?”

I’m not really concerned about what any particular lobby group is arguing at the moment. I’m here to make my own argument which is exactly as I wrote above: assuming we need to reduce our education expenditure by 20% in total from peak to trough, if we reduce teachers salaries, we can hire more of them than if we don’t.

To close, one observation and one question:

1) There’s no evidence that larger classes are associated with diminished student performance.

2) Would you be prepared to reallocate hours of teaching so that teachers taught the same amount of hours over a greater number of weeks, so that they didn’t have to work 10.5 hours a day without a break half the year? (as per anonymous teacher above)

I would be very interested in your opinion on the latter.

“So they hammer the public sector despite clear evidence that Ireland’s public sector expenditure is not out of line with international norms and did in fact decrease relative to both GDP and GNI over the boom years.”

The rest of you comments are equally invalid, but that takes the biscuit. The public sector expenditure in Ireland should have clearly decreased even more relative to both GDP and GNI during the boom years, because GDP and GNI were dependent on massive stimulous from construction which could not last. Had the government had the balls to do it, it would have said that it could not guarantee the continuance of tac receipts from construction and property related taxes, and would need to curtail the growth of Public Sector wages – and possibly increase income and other taxes ( property taxes rather than stamp duty) – to make up for it. That would have meant that teachers would get less gross pay, and pay more taxes as high earners. And the chances of that happening were the same as Hartlepool making it to the premiership and doing the triple.

Also the percentage spent on the public sector in Ireland should have been lower, we had then a lower unemplyment rate than the continentals, a younger population which should have been a smaller drain on health and pensions, and no defence budget. We spent most of what we had on wages.

“Ireland made a political choice to have fewer teachers teaching larger classes for long hours and getting paid accordingly. Critics only want to point to the salary levels and want to wave away the other aspect: large class sizes and relatively high contact hours.”

I would argue that Ireland made a polticial choice based on the demands of teachers for higher wages. A demand which made the teachers more expensive per-unit, and thus forced class sizes to be larger.

Upset with that? Lobby the union to demand pay on a “per-student contact” basis, so that you are not out of pocket.

the government can then solve the overcrowding problem by halfing your wages, and halfing the size of the classrooms, by employing twice as many teachers. The only outlay is the once off capital costs for extra rooms. The cost of the teachers in total remains the same, but we get two for the price of one. per-student contact hours are billed as before.

I dont think you would think that just. I think you want the actual high gross wages.

Hi Ronan,

That 54% disparity with Finnish teachers is striking. Do you think it might have something to do with the number of contact hours they have? This might go some way towards addressing the question of whether Irish teachers work 50% harder than Finns or not.

Eugene: For the record, I’m not a teacher so my wages aren’t at issue.

tosser: Finnish teachers are not paid 54% more than Irish teachers by any measure other than the misleading one that Ronan has cherrypicked.

Ernie, with all due respect, net pay of a teacher after 15 years service is hardly “misleading”. You might prefer gross, I can understand that, but net pay couldn’t possibly be me distorting the stats.

Tosser, good question – Eugene’s suggestion above of contact-linked pay is a good one. Ernie – would you be in favour?

Net pay most certainly does distort the stats since a large part of the disparity (visible in your graph) is the extraordinarily low tax take in Ireland relative to countries like Finland. But this isn’t a post about increasing the tax take, which it probably should be, it’s about how teachers are ‘overpaid’ in your view. Never mind if they are working longer hours teaching more kids and if a large part of the disparity in take-home pay with their Finnish counterpart is due to the insanely low tax regime here. I stand by the claim that you’re cherrypicking your statistics because they make the point you want to make.

I refer once again to the OECD report you claim to be using. On p. 453, again, you’ll see that primary Finnish teachers make US$53 per contact hour (using PPPs), lower secondary Finnish teachers make $65/contact hour and upper secondary teachers make $78/contact hour and this for teaching classes that are, on average, significantly smaller than Irish class sizes. Irish teachers, again, make $53, 66, and 66 respectively in those three categories. They are therefore, by this more honest measure, paid less (not more) than their Finnish counterparts even where lower secondary teachers here make a dollar an hour more.

But it sure sounds better when fanning populist rage to claim that Irish teachers make 54% more than Finns.

Ernie is shying away from the request to half teachers salary and half the classroom sizes. Whatever happens Teachers gross pay is sacrosanct. Taxes must increase so everybody on the graph to the left of the Education bar mus get commensurately poorer.

I think this is really a demand for the continuation of relative status, often beloved of the Public sector ( i.e if the Guards get X We must get X+10%)

Eugene, I’m not shying away from anything. You seem to still be implying that I’m a teacher when I’ve told you I’m not.

I don’t think workers in any field of endeavour would willingly embrace being told that their workload and salaries will be halved so I don’t know why you think you’re scoring points by pointing out that teachers wouldn’t go along with it.

Obviously teachers’ gross pay (and net pay) is not sacrosanct since–unlike many private sector workers–all teachers have taken a pay cut of between 6 and 9 percent of their take home. But I’m sure you won’t be satisfied until they’re working for minimum wage and then you’ll complain about how your kids aren’t learning anything. That is if you care at all about whether they’re learning anything.

How much do you suppose class sizes could be reduced if they spent the money they’re spending on NAMA on it?

“Eugene, I’m not shying away from anything. You seem to still be implying that I’m a teacher when I’ve told you I’m not.”

You are their representative on Earth seemingly.

“I don’t think workers in any field of endeavour would willingly embrace being told that their workload and salaries will be halved so I don’t know why you think you’re scoring points by pointing out that teachers wouldn’t go along with it.”

Fine. But dont try and explain away high wages with statistical chcanary – cost per student contact hour – if you dont except the outcome of their argument – that we can reduce class sizes and teacher costs at the same time since reduced classrooms means reduced student contact hours. If teachers want to keep high wages the result is higher classroom sizes, using that same argument. Which is it, concern for students or concern for pay?

“But I’m sure you won’t be satisfied until they’re working for minimum wage and then you’ll complain about how your kids aren’t learning anything. That is if you care at all about whether they’re learning anything.”

Nope, Just the European average. This private sector worker took a 20% hit this year, and may take a 50+% hit if the job goes. Private sector wages are in free fall. We all pay for pensions, until now you didnt have to..

“How much do you suppose class sizes could be reduced if they spent the money they’re spending on NAMA on it?”

Argument tu quoque. When in doubt blame the bankers.

Indeed, The bankers should be fired, lose their pensions, money should be taken bank, assets seized, banks nationalised etc. It is not either or.

Even then we have a deficit. Public Sector pay is too high, teachers are paid very well conpared to the richest countries in Europe, Ireland is no longer in that category but is tending to average. And so… reduce teachers wages.

Statistical chicanery? I can’t imagine why you think it’s statistical chicanery to want to look not simply at the wages but the work done for the wages. Simply put, Irish teachers are worked harder than their counterparts in the rest of Europe. That is why they earn more. It’s fairly basic economics. You want them to make the european average and work the european average, I assume. Has it occurred to you that this will be more of a drain on exchequer finances and not less? Or are you so enraged by misleading headline figures that such matters are of no concern to you?

I know part of your reply is that the teachers work more because they earn more, but you haven’t provided any evidence about how the nefarious teachers managed to hoodwink all of the social partners into agreeing national wage deals for their sole benefit…

Some private sector workers took a pay hit this year. Some lost their jobs. The majority did neither. Every single public-sector worker did, however, including the teachers and they pay the tax increases on top of that.

As for your final point: Irish teachers are already squarely in the middle of the pack in remuneration per hour. So, rejoice! You’ve got what you want.

[…] from Ronan Lyons (Daft economist) on the relative pay levels of teachers in Ireland and abroad. Tackling the thorny issue of teachers pay Ronan Lyons | Blog The graph showing the price per day is the most telling […]

[…] from Ronan Lyons (Daft economist) on the relative pay levels of teachers in Ireland and abroad. Tackling the thorny issue of teachers pay Ronan Lyons | Blog The graph showing the pay per day is the most telling […]

Hi Ronan

interesting post. Before I go any further, I feel it’s only proper to disclose the fact that — unclean! unclean! — I am, in fact, a primary school teacher. (Now I know how the priests have been feeling these last few years…) In spite of this, I’m optimistic that I can summon up a scrap of objectivity in replying to some of your points.

First off, I agree with you that those best able to pay should bear the greatest burden, but isn’t that the very principle already at work not only in our progressive tax system, but in the shiny new income levy too? Since teachers, like all public servants, do pay tax, and income levies, are they not already contributing in accordance with their ability to pay?

I think that your argument against teachers’ salaries, then, is not really that the ‘better off’ are not taking their fair share of the burden, but simply that teachers are overpaid. You began your case by highlighting the fact that “all the best paid sectors in Ireland are either public or semi-state industries.” This general discrepancy might have something to do with the fact that the age profiles of the two sectors do not match. Acccording to the CSO, “Two-thirds of public sector employees (67%) are aged 35 or over, compared to lesst han half (47%) in the private sector. ” [2001]

Furthermore, in answer to the question you asked above, “Some 52% of public sector employees have some form of third-level qualification,

compared with 25% of private sector employees.” [CSO, 2001] (Of course, 100% of teachers have some form of 3rd level qualification, and 100% of 2nd level teachers are post-graduates, as are quite a few primary teachers, thanks to the relatively new post-grad training courses).

So, are Irish teachers overpaid? There is no doubt that they are better paid than most, but it’s meaningless to compare what different teachers get paid without examining what they get paid for. There’s been some argument about the best way to measure the amount of work done by teachers internationally. I would say that the two key factors are the number of hours spent teaching, and the number of pupils teachers work with.

You picked out Finland as a good point of comparison, mainly because Irish teachers are paid quite a bit more, so lets have a closer look.

Others have already mentioned the cost of living differences (and not just prices: in Finland, teachers do not pay for healthcare services, such as GP visits, all citizens receive medical insurance, pre-school education is free and parents only pay a contribution towards childcare costs) that must be considered when comparing salaries.

More importantly, the average Finnish teacher spends 568 hours per year teaching. The average Irish teacher teaches 735 hours per year, while the average Irish primary school teacher spends an average of 915 hours per year in the classroom. So I might get more money than the average Finnish teacher, but they only put in 62% of the hours I do.

Irish teachers also have larger classes to deal with, so whether you count the hours they put in or the number of “customers” they serve, Irish teachers work harder, and quite a bit harder at that, than their lower-paid Finnish comrades. Looking at those figures, I can’t help wondering if some Finnish blogger is currently slaving away at a post titled: “Finnish Teachers Horribly Underworked!!!”

Whether teachers are overpaid or not, salary cuts for teachers must still be considered. Unfortunately, however, our education system is cheap, because our education system us underfunded – we rank 30th out of the 34 OECD countries in terms of the percentage of GDP (4.6%) that we spend on education. (Finland, by the way, spends 6%, reflecting a policy of investment that they stuck with through their own economic crisis). This means that, without hitting salaries, we don’t have a lot of room to make cuts – which is why the cuts that have been made have been so harshly, and rightly, criticised.

Of course, cutting salaries again (the pension levy is a misnomer – it has nothing to do with pensions) will have an inevitable knock-on effect on services anyway, despite your argument to the contrary, as recruitment and retention, not to mention morale and motivation, would only suffer further. And the idea that teachers should be happy to halve their salaries in order to halve class-size is simply nonsense. Teaching is not, despite what some might have heard, a vocation. It’s a profession. I make no apologies for expecting a decent salary and conditions – I know my own worth and how hard I work.

But maybe we should follow the Finn’s lead, and, in tough economic times, make an investment, not a cut, in education.

Hi John, thanks very much for reading the post and comments and taking the time to write such a well-thought out and thorough comment. I won’t go through everything bit by bit, but my overall response would be as follows. Primary is only half the education sector – not even, actually, when VECs and tertiary are included – so the stats you give are true but not fully representative. (My sense from the statistics is that of all three under-18 education subsectors, primary education do indeed work longest, while lower secondary work shortest.)

Two questions:

Would you be interested Eugene’s suggestion above of linking pay to contact hour? So if contact hours are changed, pay is changed. That might free up resources by, for example, a 10% reduction in pay allowing 10% more teaching.

Would you be interested in my own suggestion that teaching hours could be spread across the year in a more balanced way, allowing teachers greater time to prepare, assess and be assessed themselves on an ongoing basis? Holidays might be shorter but that would bring us back in line with the rest of Europe and ultimately three months holidays are not a right.

Thanks again for the comment,

R

Despite it’s flaws, the Irish edcation system is regarded as one of the best in the world. I would imagine that if teachers pay is reduced to match levels across Europe that this will bring about considerable changes in the Education system. People seem to be forgetting teachers are human beings. For me personally, if my job (which, by way requires a relatively high skill level) is reduced to minimum wage my extra hours wll spent on my new second job & not on training teams, running homework clubs, marking tests or planning lessons.

As well as that, teaching is a very public job. Ask any teacher out there & they will tell you that teachers face a much higher level of public scrutiny from parents, boards-of-management, priests and even colleagues. More-so in Ireland than in other countries. For example, any teacher in a country school in Ireland will (and I am speaking from experience) be quizzed on why they were no a mass at the weekend. Teachers are, rightly or wrongly, answerable to parents. This creates the question, if the pay of the average teacher is dropped to the levels you are suggesting would such scrutiny be worth it?

On a side note, I will be qualified next year and don’t anticipate earning anything close to the national average for quite some time.

Hi Rory, thanks for checking back in. No-one is arguing that teachers should only be paid minimum wage. I think (hope?) the argument is that their pay should be benchmarked, either to people with similar skills in Ireland or people in similar jobs elsewhere.

On your last point, if I follow your implication, I’m not sure why you would expect to earn the national average wage with no experience… surely you (and I and everyone) would have to work up to the average and achieve it broadly speaking when experience and qualifications match the national average.

Perhaps you might do some research on relative class sizes. Why are there no graphs on class sizes?

Of course it would not suit your argument.

Why have you not become a teacher yourself? Far off hills are always greener. You speak about pay cuts for teachers. What planet are you living on? Teachers pay has been cut by levies totalling 11%. Call it what you like but teachers pay has been cut.

Question for you: Please outline the extent of pay cuts for bank workers?

Please furnish some graphs re pay at THIRD LEVEL and also number of hours worked.

Can we have some graphs on politicians pay and payments to top bankers and builders over the last 7 years.?

You say: “To close, one observation and one question:

1) There’s no evidence that larger classes are associated with diminished student performance.” Please furnish data to substantiate this statement. Are you saying that each student in a class of 30 will enjoy the same prospects of progressing as each student in a class of 22?

You make no allowance for discipline problems in larger classes. Your statement is a fallacy.

I’m not a teacher of maths, but this strikes me as a disingenuous presentation of the data. Let’s take only one example.

Bingo. Bankers make less than soldiers? Yeah, right.

I’m dumping this blog from my RSS feeds in disgust – I can at least get honest stats from Gurdgiev, no matter what interpretation he puts on them.

Hi EWI, I’m not sure what’s offended you so much – all I did was use CSO and OECD stats to compare salaries in education in Ireland with other sectors here and with other education sectors in Europe. The OECD stats are “honest” and I would encourage everyone to go and use them – as I say in the post, although judging from your comment, I think you may have read the comments rather than the original post itself.

Well firstly, I agree that one works up to the national average through gaining in experience and qualifications. That is undeniably fair.

But, I am curious, what profession would you consider to be of similar skill level to that of teaching?

[…] pointed out in my comments on Ronan Lyon’s original thread here and here and here why his statistics are misleading to the point of verging on dishonesty, […]

A related question: what professions in Ireland don’t earn higher salaries than their European or OECD counterparts? My guess is that almost all of them do. Which leads me to wonder why certain quarters are obsessed with what teachers earn.

Don’t worry, I’ll be having a look at other sectors too! All in its own good time…

I’m not here to make friends, I’m here to do honest research.

PS. Ernie, I believe you’re not a teacher! Coincidentally, and for full disclosure, I do actually have a close relation who works as a teacher. (Cue the “Many of my best friends are teachers” line!) And, while we seem to disagree on pretty much all our conclusions apart from government mismanagement of public finances, I couldn’t agree with you more on this sentiment: “I’m interested in the truth and that is my sole motivation here.”

“A related question: what professions in Ireland don’t earn higher salaries than their European or OECD counterparts? My guess is that almost all of them do. Which leads me to wonder why certain quarters are obsessed with what teachers earn.”

I seriously doubt you are not a teacher.

the protected sector professionals probably earn more than most europeans but wisely stay quiet. the tradable professionals earn less than the developed European states – I for instance and engineering are better paid in Germany.

I seriously doubt you are not a teacher.

I’m afraid I’ll have to insist. I am not a teacher. My wife is not a teacher. Nobody among my immediate relations is a teacher. One sister-in-law is a teacher but I don’t know her that well though I believe she works very hard.

As for the rest of your post: a whole farrago of ideological nonsense can be built on what ‘probably’ is the case just as it can on what ‘everyone knows’. Like: ‘everyone knows the teachers here are overpaid’. I am not interested in what passes for common knowledge among you and the knights of ressentiment you hang around with. I’m interested in the truth and that is my sole motivation here. Pity that others are not.

“I am not interested in what passes for common knowledge among you and the knights of ressentiment you hang around with. I’m interested in the truth and that is my sole motivation here. Pity that others are not.”

Feel free to work it our on google youself then. I can clearly see that jobs in germany for engineers are higher than in Ireland. But I cant really be assed looking those figures up for you. Clearly those of us for work in the unprotected sector have to compete internationally so we cant afford to overpay ourselves as much as the mollycoddled Public Servants. Ronan will produce the results as he said: I already know that consultants earn more than anywhere else.

“I am not interested in what passes for common knowledge among you and the knights of ressentiment you hang around with. I’m interested in the truth and that is my sole motivation here. Pity that others are not.”

You cant handle the truth. I, and Ronan, have asked many times whether if teachers pay in Ireland should be measured on a per student contact hour we could reduce classrooms sizes and teacher pay. If you recall you were the first to introduce this term to overcome the clear evidential facts – linked to by by Ronan – that Irish teachers are amongst the highest paid sectors in Ireland, and the highest paid teachers in Europe. You are losing this argument my friend, and entering into ad hominem attacks.

as for whom I hang around with: often as not public servants, teachers, and consultants amongst other private sector profressionals – it is a small country. At least one of these admits his is overpaid. Not the teacher(s). Or course.

Unfortunately for you, one doesn’t win an argument simply by insisting that the other side is losing. I stand by my claims which have been backed with evidence and not refuted by Ronan and certainly not by the likes of you. To wit: that Ronan’s figures are misleading, that, contrary to what you say, the facts show that Irish teachers are not only not the highest paid teachers in Europe, they are not even close. The claim that they are the highest paid rests on a complete unwillingness to consider their workload both in terms of hours and students ‘served’. That’s about as intellectually dishonest as comparing the salaries of full-time workers with part-time workers in order to argue that the full-timers should take less pay. You’ll forgive me for not feeling that that’s an argument worth having with a boor.

Pronsias (9pm last night) wrote:

“You say: Please furnish data to substantiate this statement. Are you saying that each student in a class of 30 will enjoy the same prospects of progressing as each student in a class of 22?

You make no allowance for discipline problems in larger classes. Your statement is a fallacy.”

With all due respect, I would suggest that you’re not familiar with the literature. A leading author in this area is Erik Hanushek – one of his most widely cited papers is this one: http://www.jstor.org/pss/2138552. It shows that on balance, the evidence is that there is no concrete relationship between class size and pupil performance.

To quote directly: “It would at the very least be an embarrassment, and at the worst a potential policy disaster, to find that variations in resources devoted to schooling are not the primary factor determining student performance. But that appears to be the case. Three decade of intensive research leave a clear picture that school resource variations are not closely related to variations in student outcomes.”

Ronan,

Is it typical among economists to present the findings of a single researcher (and a right-wing ideologue at that) as though they were the final word on whatever subject is under consideration? If so, that might go some way to explaining how we were led into the sorry predicament in which we now find ourselves. Is being familiar with a single, highly-controversial author’s work what you call being ‘familiar with the literature’? And if this is what you consider a correct way to proceed in such matters, how do you reconcile that with your claim to be interested solely in the truth?

Off course Hanushek is hardly the last word on the subject as 30 seconds spent perusing Google would make clear. For example:

Click to access 451.pdf

Click to access 543d57e139a7bcc422_vnm6b5tkc.pdf

Click to access edu972214.pdf

And since we’re ‘quoting directly’ allow me to quote the abstract of the last article:

‘This investigation addressed 3 questions about the long-term effects of early school experiences: (a) Is participation in small classes in the early grades (K–3) related to high school graduation? (b) Is academic achievement in K–3 related to high school graduation? (c) If class size is related to graduation, is the relationship explained by the effect of participation in small classes on students’ academic achievement? The study included 4,948 participants in Tennessee’s class-size experiment, Project STAR. Analyses showed that graduating was related to K–3 achievement and that attending small classes for 3 or more years increased the likelihood of graduating from high school, especially among students eligible for free lunch. Policy and research implications are discussed.’

Impressive, isn’t it?

So, either you’re not aware that there’s a healthy debate on the subject–which makes you incompetent to make pronouncements about it–or you’re being an intellectual hatchet man. Which is it?

And can I assume you’d be delighted, on the strength of a single man’s research (no doubt paid for by a right-wing think tank) to send your own kids to a school where they were packed 150 to a class?

Hi Ernie,

You summoned up the energy I failed to in replying to the original comment. I could be equally as emotional and make the exact opposite case, arguing so and so was funded by a left wing group, etc etc. My overall point was that the original comment-maker seemed completely oblivious to the literature. I gave a quote that I hoped would make him think about his prior position a little more critically, as you are urging me to do. The evidence on class size is very mixed, as you no doubt well know but won’t say.

To answer your question, everything else being equal, I would prefer smaller class sizes for my children. In the real world, everything else is not equal. Therefore, school quality and teacher quality for me are the more important criteria. I was taught in classes of 10 and classes of 40 and at the time and now looking back, class size pales into comparison next to teacher quality.

I’d rather have my kids in a class of 150 with an excellent teacher than a class of 15 with a rubbish one. You?

Oops. My ‘healthy debate on the subject’ link was supposed to go to this. Here’s a choice quote from it:

Nevertheless, enough of these surveys had ap-

peared by the late 1970s that reviews seemed to

be in order, and in the early 1980s Eric Hanushek,

also an economist, began to publish a series of

articles reviewing these works and discussing their

supposed implications. Hanushek seems to have

been committed, from the beginning, to a version

of economic theory that argues that public school

are ineffective and should be replaced by a market

place of competing private schools, and it is small

wonder that his reviews have regularly concluded

that differences in public school funding — as well

as things that funds can buy — are not associated

with educational outcomes. Most of the studies

Hanushek has reviewed did not provide evidence

on class size, but some seemed to focus on the

class-size issue, and after reviewing the latter as

well, Hanushek has announced that class size also

appears to have little impact.

However, Hanushek’s methods and conclusions

have been challenged on several grounds. Meta-

analysts, such as Larry Hedges and Rob Greenwald,

have pointed out that Hanushek merely counts the

number of effects he finds that are “statistically sig-

nificant,” but since most of those effects are based

on studies with small samples, it is nearly inevitable

that he would find but few “significant” effects. In

contrast, when those effects are added together in

meta-analyses, the overall results suggest that dif-

ferences in school funding and those things that

funds can buy — such as smaller classes — do,

indeed, have an impact.

Another economist, Alan Krueger, has also ob-

served that Hanushek does not base his findings

on the number of studies he reviews but rather on

the number of different findings reported in those

studies — a procedure fraught with potential bias —

and that results supporting the importance of class

size pop up quickly if one corrects for these biases.

And several commentators have pointed out

that many of the supposed “class-size” studies

Hanushek reviews do not examine class size directly

but rather a proxy measure presumed to represent it

— student-teacher ratio, defined as the number of

students divided by the number of “teachers” report-

ed for a school or school district. The troubles with

this latter measure are that it ignores how students

and teachers are allocated to classrooms and often

includes counts of administrators, nurses, counsel-

ors, coaches, specialty teachers, and other profes-

sionals who rarely appear in classrooms at all. Such a

ratio is, then, a poor way to estimate the number of

students actually taught by teachers in specific class-

rooms, and it is the latter we need to know about if

we are to study the effects of class size.

Hanushek has not responded well to such criti-

cisms; rather, he has found reasons to quarrel with

their details and to continue publishing reviews,

based on methods that others find questionable,

which claim that the level of school funding and

the things those funds can buy — such as smaller

classes — have but few discernable effects. These

efforts have endeared Hanushek to political con-

servatives who have extolled his conclusions, com-

plimented his efforts, and asked him to testify in

various forums where class-size issues are debated.

And in return, Hanushek has embedded his conclu-

sion about the supposed lack of class-size effects in

a broader endorsement of a conservative education-

al agenda. Given these activities and allegiances, it

is no longer possible to give credence to Hanushek’s

judgments about the impact of class size.

Sounds like your kind of guy, Ronan.

To answer your question, everything else being equal, I would prefer smaller class sizes for my children.

In other words, controlling for everything else, class size does matter, even to you. Which means you’re promoting ideas that you don’t believe. One can only wonder why you’d do that.

At the risk of getting into a shouting match in an empty room, I would have thought I was being clear, even to you.

Class size is a nice-to-have, not a must-have. I would happily sacrifice it if there were a choice between class size and teacher quality. You?

And how do you reconcile this statement:

The evidence on class size is very mixed, as you no doubt well know but won’t say.

with this one:

there is no concrete relationship between class size and pupil performance.?

I hardly think you’re in a position to be accusing me of knowing things that I won’t say, especially given that you’re responding to a post in which I wrote that ‘there’s a healthy debate on the subject’ and linked to several studies, two of which attempt to review the literature.

Class size is a nice-to-have, not a must-have. I would happily sacrifice it if there were a choice between class size and teacher quality. You?

I wouldn’t consider myself able to make blanket pronouncements about false dichotomies.

Class sizes are way off topic.

In fact – for the 4th time – if we want to reduce class sizes we can reduce teachers pay, and hire more teachers. That will stop the “overworked per student contact hour” malarky.

However the class size issue is symptomatic of how teachers, and their representatives on Earth like Ernie, fudge the issue. We are now arguing class size, not pay. Why?

In fact – for the 4th time – if we want to reduce class sizes we can reduce teachers pay, and hire more teachers. That will stop the “overworked per student contact hour” malarky.

I have a better idea. If we want to reduce class sizes, we can have a special tax on engineers and use the proceeds to hire more teachers.

but of course Ronan doesn’t want to reduce class sizes. That would be pointless in his view. He just wants to cut teacher pay based on evidence that he has, after some serious effort, managed to cherrypick and twist into the false claim that they are overpaid.

@Ernie – I think we have your point of view Ernie to be honest. As a reader with an interest in genuine discussion and debate I wanted to read comments on the post to inform myself better and gain a deeper understanding of the issue. Teacher’s pay is as Ronan puts it “a thorny issue” – and is unfortunately usually debated as a black and white – with one side crying “long holidays, overpaid – stop moaning teachers” and the other crying ” underpaid overworked – poor teachers”

The reality, as always, is somewhere in the middle. And by reading this post and the comments I had hoped to gain a better understanding of the points of view, and be able to form a more informed personal opinion of where I believe the reality to lie.

Unfortunately I was disappointed in this by the sheer bullishness of your comments and seeming desire to exhaust any other commenters. Frankly my patience was so sorely tried that I was moved to comment myself!

I would suggest that rather than just trying to “win” the debate by using derogatory comments, emotive language and generally attempting to exhaust everyone into submission. That you start your own blog and post your above arguments in a proper forum. Perhaps you have one – could you direct me to it? Comments are supposed to be comments, not essays (although this has turned into one 🙂

And before you accuse me of being of the Irish-Independent-FF-anti-teacher etc brigade, let me assure you I am not any of those things. I am simply someone trying to develop my understanding of interesting and complex issues in the public domain, and to form my own opinion and in fact I may well agree with most of your general argument, but frankly you’re doing your own cause a disservice by not knowing how to let other people speak.

I’m not interested in exhausting you or any other commenters. But I think that the truth of the matter is important enough to debate at length. ‘Thorny issues’ are, almost by definition, those that require teasing out and that requires dialogue, sometimes extensive dialogue.

As for emotive language and derogatory comments, I apologise. But I tend to get worked up about intellectual dishonesty in the service of an ideological agenda. Insults directed at Eugene were retaliatory.

In any case, Ronan hasn’t bothered to answer my substantive objections about his manipulation of the OECD data to suit his biases. Far from presenting the ‘thorny subject’ in its nuance and complexity, Ronan seem content simply to bash through the fine points and hope nobody looks too closely at the results. I don’t consider that to be an intellectually honest way of proceeding in such debates which are, I remind you, of crucial importance to Irish society today.

In short: this is what ‘genuine discussion and debate’ looks like. Are you sure you’re interested in it?

What “ideological agenda”? I have missed this, if it exists. I see an argument against teachers being paid as much as they are. From looking around the blog I don’t see any ideological position shining through.

What’s your ideological agenda as we’re on the subject? I understand you’re not a teacher but you seem very fixed on this position – are you from a union by any chance?

And “intellectual dishonesty” is a fairly inflammatory thing to say.

I can’t believe you have me arguing with you, when I largely agree with you on the principles.

This isn’t genuine discussion and debate. This is annoying, and as I mentioned before – exhausting.

Why don’t you move the debate to irisheconomy.ie – there are people there who could provide some good insights.

You don’t recognise the ideological agenda? Let me spell it out. How and why has it come about that, suddenly, the public sector is in the crosshairs of virtually every major media outlet? To read the papers, you’d think that the public sector caused the current mess. They didn’t. What’s happening here in this country today (but not only here) is that the freewheeling and unalloyed faith in the virtue of markets as not simply one means, not even the best means, but as the only means for apportioning rewards and punishments and of allocating resources has been dealt a death blow. Unjustified faith in the self-regulatory power of markets (and concomitant suspicion of regulation, which was almost a dirty word in the Bertie/Bush years) is what led us to this terrible economic calamity.

The people who embraced the ideology by which the market is the sole source and arbiter of all virtue–Fianna Fáil and PD politicians, IBEC, the Independent Media Group, right-wing economists of all sorts–are now doubling down. For it can’t be that the market failed! It just can’t be! Something else must’ve gone wrong. What could it be? Wait, I know! It wasn’t that we relied too much on market forces to make judgements that are best left to human beings. No! It’s that we didn’t rely on them enough. We were betrayed by those parasitic leeches in those parts of the society that are not governed by market forces but, rather, by some high-minded ideals of human service. Yes, the public sector! That’s our problem!

Get it? The problem is not that people’s old-age pensions have been given over to market forces with the result that many of them have been bankrupted and will be living out of cardboard boxes despite having paid thousands into them. That’s can’t be the problem because we know that all virtue resides in submission to such market forces. Therefore, the problem is the remaining part of the pension system that has not been given over to market forces and has not, as a result been bankrupted. That’s the problem!

Do you get it now? The very same people who complain about layoffs and pay cuts and bankrupted pensions in the private sector, rather than seeing the causes for what they are (excessive faith in the virtues of markets) insist instead–in a peculiar blend of Milton Friedman and the age-old tradition of Irish begrudgery–that the problem is rather that such insecurity and bankruptcy has not been universally applied. That’s the problem!

Can you see why this is an ideological agenda? Ronan, who just happened to decide out of disinterested intellectual curiosity that Irish teachers’ pay was an interesting subject of investigation and just happened to present the existing international data in a way skewed to present those teachers in the worst possible light, is a participant. This blog doesn’t take place in a vacuum and its context is, as I’ve said before, the relentless media hammering of the public sector by those vested interests most of whom couldn’t care in the slightest about public sector reform because they wouldn’t mind seeing the whole sector abolished if they thought it would make their taxes lower.

And let’s be clear who the antagonists are. The public sector is made up of people who serve others, who teach them, protect them, care for them. Those advancing the attack against them serve only themselves. If there’s money to be made concocting a new and more efficient Death Gel, they’re all for it. It adds to the nation’s ‘growth’ don’t you know.

The fact that you don’t even recognise this ideological agenda for what it is is symptomatic of how deeply ingrained it has become: it is the very air we breathe. The fact that it is noxious is something we’ll never notice until we step outside.

OK Ernie, I think you’ve well and truly had your say at this point. I won’t bother retorting in detail – hopefully my series of posts on the Irish economy weekly from now on will be rebuttal enough. I think it’s certainly been an eye-opener for me that there is this level of resistance to analysis.

I’ll have a fresh post up in the morning – this time on the world economy.

Hey Ronan

I think most of the damned lies, eh, I mean stats, I used were, in fact, representative. For example: I referred to the age profiles of the public sector vs private sector (67% aged 35+ vs 47%), and respective levels of educational achievement, (52% with 3rd level qualifications vs 25%), which would account at least in part for differences in average wages between the two sectors overall.

I quoted both overall averages as well as figures just for Irish primary school teachers when discussing contracted hours per year, although the percentage I gave only represented primary school numbers. Using overall averages, Finnish teachers teach for around 77% of the hours Irish teachers do.

I didn’t mention any figures relating to class size, because I couldn’t find any for Finland. What I do know is that the maximum class size in Finland is 20. Only 10% of Irish children know what it’s like to be in a class of less than 20, while 20% are taught in classes of more than 30. I’m sure the overall figures are a bit lower, since the average class size in a primary school is 24.5, whereas at second-level it’s 20.1.

I know there are differing opinions among academics about the impact of class size on educational attainment – I suspect that if there is anything like a consensus it would be that it matters, quite a lot with younger children, and less so as they get older. In my short teaching career, I’ve experienced working with a small class of 16 and a larger one of 26, which although not high by national standards is quite high for a DEIS (band 1) school like ours. In my experience there is no question that it’s is far more difficult for me to cater to the needs of all my students in larger classes. By that I mean that I have less time to spend one-to-one with pupils, and more time is lost to classroom management issues and discipline issues.

That doesn’t mean that I would be in favour of giving up half my salary in order to halve class size. Firstly, the ‘half n half’ idea is completely unworkable. The construction and maintenance costs of doubling the number of classrooms in the country would be astronomically prohibitive, especially in light of the fact that we can’t even keep the rats out of all the schools we currently have.

It’s also counterproductive. The fact that you’d then be trying to hire people with between 3 and 6 years of 3rd level education to do a highly demanding job for an average salary of less than €30k might just maybe lead to some recruitment and retention problems. To put it another way, under this idea, the cost of teachers salaries would remain the same, and while you would have smaller classes, you’d also have rubbish teachers. Given that, I’m surprised that you have any interest in the idea.

Generally, I don’t think the idea of linking teacher’s pay to contact hours is a good one. There is, and always will be, a wide variation in actual class sizes in schools around the country. For example, 10% of classes are under 20, while 20% are over 30. Paying teachers more for teaching bigger classes would lead to all the best teachers working in the schools with the biggest classes. Since class size can also vary greatly within any given school, teachers would find their salaries increasing or decreasing dramatically year by year.

Pay per contact hour would also mean that teachers who work in resource, learning support, language support or with special needs children would only earn a fraction of mainstream class teachers. In any event, much of the extra work that large classes demand of teachers is not paid for at all, since it occurs outside of school time when teachers prepare lessons or correct students’ work.

Like many teachers, I have a professional interest in our education system, and ideas about what might make it better. Like all teachers, I already contribute my fair share towards the cost of education in Ireland when I pay my taxes, the same as everyone else in the country. If there is a responsibility to fund a reduction in class size, that responsibility rests on every citizen of the state, not exclusively on teachers. Any salary reduction for teachers should only be considered in light of the realities of the current economy and the overall size and cost of our public sector.

I’m not sure what the benefit of a re-structured school year would be, apart from making life easier for some parents during the summer months, perhaps at the cost of a shorter school day making life more difficult for the rest of the year. The Dept of Education seems to have plenty of time to evaluate schools, while I think most teachers find it far more useful to have their non-contracted hours in a “lump-sum” rather than spread out day by day during the academic year. And children, I think, benefit hugely from having a long break from school, where they can get on with the important business of simply being children, without the interference of teachers.

Again, I am not arguing against the idea of examining a reduction in the wage bill either of teachers or of the public sector. But ideas like halving teachers’ salaries to reduce class size, without actually reducing the overall wage bill (and incurring unimaginable infrastructural costs at the same time), or restructuring the school year, without lowering the wage bill, for no reason other than the fact that there is no universal right to three months of holidays, or imposing an ethical imperative exclusively on teachers to accept a wage cut in order to fund investment in education are not going to move the debate in a positive direction.

Hi John,

Thanks for the comment.

You said: “Generally, I don’t think the idea of linking teacher’s pay to contact hours is a good one.” However, Ernie was arguing that teachers in Ireland are good value precisely because of this metric, so unfortunately it can’t be spun both ways – i.e. that teachers pay is good value by metric A, but that teachers pay shouldn’t be judged by metric A.

You also wrote: “Most teachers find it far more useful to have their non-contracted hours in a “lump-sum” rather than spread out day by day during the academic year. And children, I think, benefit hugely from having a long break from school.” I think that’s interesting because teachers often argue that one the downsides to their job and one of the reasons they represent good value per hour work is because they work such long days (anonymous commenter earlier saying >10 hours a day). It’s also interesting because schools in most other eurozone states have made the judgement call the opposite way. (That call in and of itself doesn’t prove anything, but does suggest it’s worth looking into.”

I’m hoping to return to the education sector in a few weeks, after I’ve had a look at a few other aspects of the Irish economy – which was my intention all along and which posters on politics.ie, boards.ie and a few other places seem keen for – so I hope to address some of these issues in more detail.

Thanks,

R

I know you’ve probably had enough of this topic by now, sorry!

Just to clarify, there’s a difference between judging teachers pay by the metric Ernie outlined, which I think is useful, and linking individual teachers’ salaries to that metric, which would be a disaster. What I mean is, it makes sense to look at the average figures to see what kind of value for money the state is getting: how many hours of instruction are received by how many students, and at what cost. But to say that individual teachers’ salaries should vary according to the number of pupils they teach (since the number of hours, within each level, would be the same for every teacher) would be a mistake.

You are right that teachers work more hours than those they spend in the classroom and are directly paid for, although I would argue that teachers deliver value for money even without factoring in the hours of voluntary work teachers undertake. This would remain the case even if the school day was shortened and the school year lengthened, because the overall contracted hours would remain the same. For these exact reasons, having long stretches of time off from school at Christmas, Easter, Summer etc is far more useful to teachers than loads of little stretches of time off day by day during the academic year. Absent any pressing reasons, I don’t really see any value in restructing the school year.

[…] Ronan Lyons does some analysis of pay levels for teachers here. […]

I enjoyed reading your analysis and the discussion here. As I live in Holland I have a slightly different view on the Irish situation.

1) In terms of your ‘half and half’ idea. In Holland the majority of primary school teachers are women and work part-time. That effectively means that they earn about half of what their full-time counterparts earn. Maybe increasing the number of part-time teachers in Ireland would be a way to increase the number of teachers and lighten the 10 hour days during the school year.

2) Whatever the relationship between class size and pupil performance it is almost certainly not directly proportional. Obviously at a certain point classes are unmanageable but other factors come in to play such as teacher quality as you say. Moreover, pupil quality also must be a factor, learning is also dependent on peer to peer interactions. My daughter goes to a Dalton school where older children often help the younger ones with tasks. My daughter goes to a Dutch school but speaks English so I imagine that this resource will be used in time just like the quality of Irish I learned at school was helped by having native and near native speakers in my class.

3) There is a truism that the Irish educational system is one of the best in the world but I don’t see this being backed up by statistics. Finland regularly tops charts for educational performance, is Ireland’s performance really so good? My own main area of interest is languages and anecdotally the evidence I see working in an international environment is that most Irish people neither speak Irish nor any other language than English. It is picking one area but this compares poorly to say German, Dutch, Finnish and Scandinavians I come into contact with all of whom speak at least three languages.

Hi Aidan,

Thanks for the comment – great to get an external perspective! An issue I’d like to explore is whether there are great potential efficiencies in teaching all primary students through Irish – cutting down on the time spent on Irish itself and nothing else while also exposing young Irish minds to fluency in different languages – something one would expect could have a long and large dividend. Not sure what your thoughts would be on that.

I’m not really familiar with Dalton schools – sounds very interesting, must explore!

Ronan

with the ever increasing numbers of ‘international’ students attending our schools, it would be impractical to teach all subjects through Irish, even if there were sound educational or other reasons for doing so. One of my colleagues, for example, has a minority of Irish children in her class.

As things stand, Irish is allocated about 15% of the total secular instruction time in a typical Irish school( Religion is not far behind). And, of course, there are gaelscoileanna for those parents who wish their child to be taught through Irish.

Ah, you leave me and my Grand Proposition somewhat deflated!

It does bring up another topic, though – wow, almost one in three hours is devoted to either religion or Irish at primary level… That might explain why so little time is spent teaching maths and science at the same age. Can we not move religion study to Sundays?!

Personally I’d be all in favour of removing religious instruction from schools, but the vast majority of primary schools are under the patronage of the church, so I don’t see it happening any time soon.

That said, it’s not quite one in three hours devoted to Irish/religion – Irish takes up 3.5 hours out of a total of 20 hours secular instruction. There’s another 8-and-a-bit hours in the typical school week for things like breaks, assembly, roll call, etc, and 2.5 of those extra hours are given to religion.