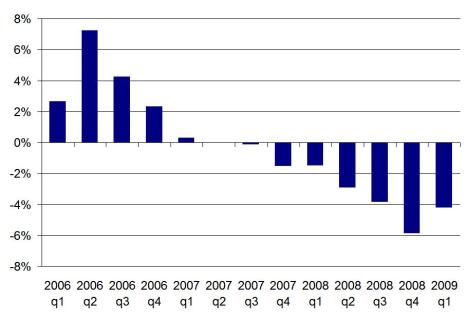

Ireland’s property slump marked it second birthday today, with the news from the latest daft.ie report that asking prices for residential property fell 4.2% in the first three months of 2009. This latest drop in prices marks the eight consecutive quarter that prices have fallen.

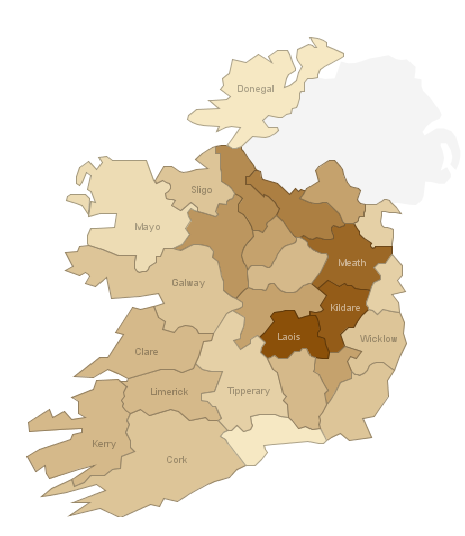

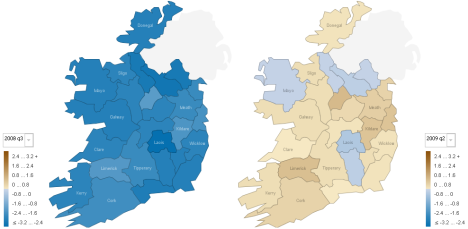

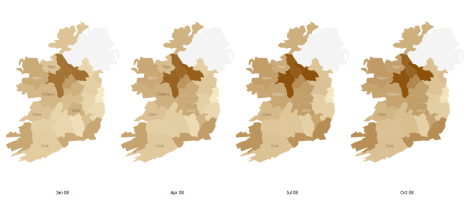

As the official press release notes, the national average asking price now stands at just over €280,000, meaning that prices have fallen almost €70,000 from the peak in early 2007. What’s interesting to note at this stage is that Dublin was worse hit on average over the first quarter – in particular Dublin city centre, where prices fell by 11%. Other notable falls since the start of the year are Sligo and Waterford city, where prices fell by about 10% in three months.

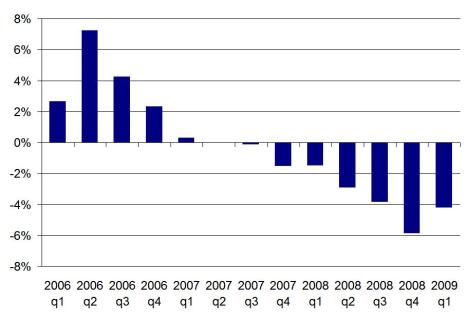

The fall in the first three months of the year should not be underestimated, particularly as the year-on-year rate of change has now slid to -15.7%. Nonetheless, a graph of the quarterly change in asking prices gives some food for thought. The falls in house prices got worse and worse more or less every quarter from mid-2007 on – until now, as the diagram below shows. How much we can read into this, though, will have to wait until next quarter, when we can see if the trend continues.

Change in national average asking price from quarter before, source: daft.ie

Commentator for this report is Liam Delaney, a behavioural economics expert. He discusses the importance of psychology – and the value in terms of self-worth of things like owning a house or having a job – in current economic conditions. He draws an important distinction between public and private sector workers (or at least that’s how I interpret it):

This report – combined with the recent labour force figures – indicates considerable hardship for those in once solid middle-class jobs that are now facing a potential double-whammy. People will inevitably feel even worse when they see neighbours and friends who are in better situations. Consider the position of a college graduate who purchased in Dublin in 2006, based on the income from his financial services job (now gone), to the position of his neighbour who secured a public sector position on leaving college and purchased in 2001. While neither is laughing, the latter must at least be considering himself the better off of the two. They are certainly not in the same boat and the widening rift in society being generated by asset price decline and employment uncertainty is the defining theme of our time. As described by John Fitzgerald and others, there are many who are currently better off than last year, as they are facing declining prices and interest rates in the context of stable employment in their sector.

He also describes two scenarios for the future, drawing on Gerard O’Neill‘s own commentary on a previous Daft report, where he suggested that the current economic maelstrom in which Ireland finds itself is probably the only thing that could possibly ever turn Ireland into a nation of renters – the implication being that may just happen. Liam then walks through the implications of these two scenarios:

One version of a national narrative that was articulated in the previous commentary by Gerard O’Neill was the idea that the Irish cultural and psychological need for property may be displaced by a culture where renting is given more credence as part of a normal adult life. Were such a story about the Irish relation to property to take hold, it would clearly have substantial implications for any potential future rebound in property prices. Key players at the moment are those who can afford property but are riding out the current uncertainty by taking advantage of falling rents. If they follow Gerard’s story, they may never come back into the buying market and the next generation may follow them into long term renting.

Yet, we still hear strongly the story that the Irish have always been and will always be wedded to the idea of home ownership as a fundamental part of maturing into adulthood. If such a story about Irishness and adulthood maintains its hold, house prices will eventually settle at a higher level, and changes in the market will depend on macroeconomic conditions, rather than on the type of seismic shift in Irish culture described by Gerard.

I’ll be posting each day this week on different findings from the latest figures, starting tomorrow with a Budget-day special… did someone say an Irish property tax? Later in the week, I’ll also look at the stock of property for sale – which incidentally has now fallen, however slightly, each of the last six months – but before I do, a quick comment on asking prices versus closing prices. Accurate measurement of house prices is a hot topic at the moment – it seems the ptsb closing price index reached a minimum fall in year-on-year terms of 10%, while asking prices haven’t yet found their nadir.

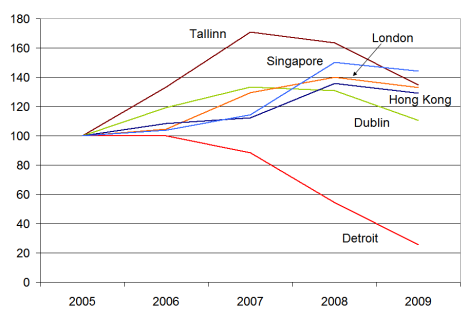

Changes in asking and closing prices, 2007-2009

The full report is available at www.daft.ie/report and contains, as mentioned above, a commentary by Liam Delaney, Lecturer in Economics with the Geary Institute, UCD, as well a regional and county-by-county analysis of the latest trends in the property market.

Filed under: 3 Property Market | Tagged: 3 Property Market, daft, daft report, daft.ie, dublin, ireland, irish property market, irish-property, irish-property-prices, liam delaney, property-prices, ronan lyons, sligo, thepropertypin, waterford | 5 Comments »