On Monday the latest daft.ie report came out, showing that asking prices had fallen just over 4% in the first three months of the year. Yesterday, I changed focus on the blog a little, as it was Budget day, and tried instead to put some numbers on what a potential property tax could raise.

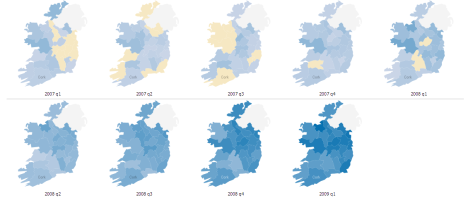

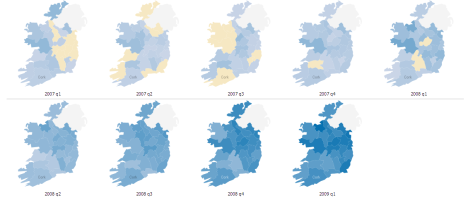

Today, I hope to give a little more detail on the findings from the report itself, in particular regional trends, and then give an international perspective also – or at least start to give one, which I think is always instructive. Below is a graph showing the quarter-on-quarter change in asking prices for the last two quarters, i.e. Q4 2008 and Q1 2009, in each county. The most obvious finding – probably not a surprise to anyone – is that asking prices fell in almost all counties in both quarters. A second clear finding is that there does not appear to have been one or two counties more affected in the last six months than elsewhere (although one could make the argument that Munster has got off relatively unscathed since September).

Quarter-on-quarter changes in house prices, 2008q4-2008q1

What also jumps out is that the two quarters saw very different patterns. In the final three months of 2008, a few counties – such as Galway, Westmeath and to a lesser extent Donegal and Leitrim – saw the largest downward adjustments in asking prices. Two counties, Mayo and Tipperary actually saw no fall in their asking prices. This quarter, Mayo and Tipperary actually had slightly larger falls than average – perhaps a sign that sellers there had been holding for the start of the year before acceding to the realities of the market. On the flip side, sellers in Galway and Westmeath believed in Q1 that their large adjustments in late 2008 did not need to be followed up with more adjustments straight away.

Sligo has been the worst hit county in terms of falling house prices, with a fall in the region of 10%in three months alone. (Dublin city centre and Waterford city actually saw bigger falls but they are lessened by other parts of their counties.) Aside from that, it seems that Dublin generally and the counties around it were among those with larger adjustments since the start of the year.

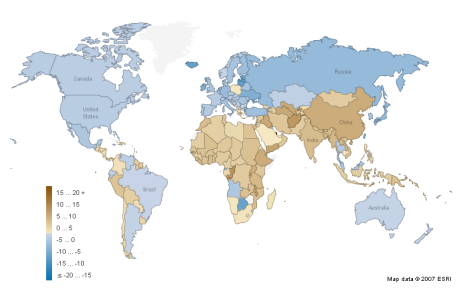

This leads on to perhaps a more interesting question – how have counties fared since their property prices peaked? To do that, I’ve set up another Manyeyes dataset (which anyone can access) with the percentage gap between house prices in a given quarter and the peak, for each county. Where a county is sandy coloured, that means it has peaked. The deeper the blue, the bigger the fall. (One little trick with these figures is that for a county’s earlier “blues”, prices are still going up. By the second row, that’s no longer an issue.)

Change in asking prices from the peak, 2007-2009

A couple of findings emerge, based interestingly on alternate axes of the country:

- East peaked before west, on average, and by almost six months. If you draw a line from Cavan down to Wexford, 10 of the 13 counties peaked in the first half of 2008, more than half the country in population terms, including all of Dublin and its offshoots. Cork, Galway, Limerick and a few other counties actually peaked in the second half of 2007, while a couple of stragglers – Tipperary and Westmeath to be precise – only peaked in early 2008. (Interesting to note, in passing, their sellers’ totally different reactions to conditions in late 2008, as per the first chart above.)

- North is falling faster than south, on average. If you draw a line from Dublin over to Galway, 9 of the 10 worst affected counties so far come from that half of the island. The top half of the property market – literally! – has been lopped off more than the bottom half. This means that the north-east – essentially Dublin-plus – fell first and is falling hardest, while the south-west – Munster – was last to fall and has fallen least so far. It will be interesting to compare these emerging trends, two years into the property crash, with the final statistics on Ireland’s property readjustment/crash/Armageddon/return to sanity/fill in name here.

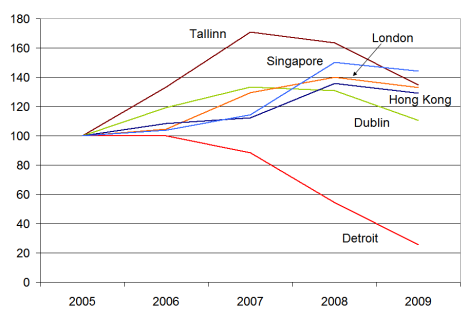

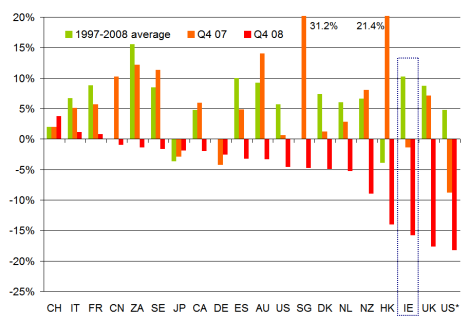

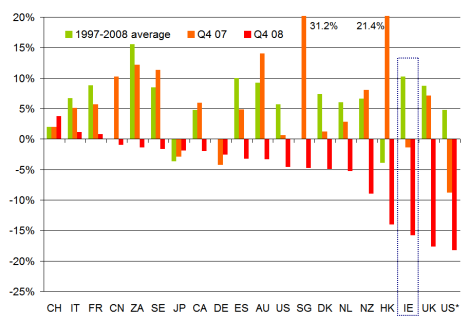

Speaking of writing the history books, perhaps it’s no harm to have a quick look to our left and our right and see how other property markets are faring. Below is a chart of about 20 countries (with two different measures in there for the US, the first is the OFHEO measure, while US* is the Case-Shiller national index). I’ve based this on data posted on the Economist’s website, but have surreptitiously replaced the 2007/2008 ESRI data, about which there is a lot of scepticism currently, with daft.ie data. The bars show the annual rate of change in house prices, including a 1997-2008 average, and figures for 2007 and 2008. (As per the Economist website, some of the Q4 08 figures are actually Q3 08 while a couple, including Ireland, are Q1 09.)

International comparison of property markets, 1997-2009

Replacing the ESRI data with the daft.ie had the effect of moving Ireland from the “Club of Moderates” such as Denmark and the Netherlands, to the “Bleeding Edge” group with Hong Kong, the UK and the US (at least one measure for the US at any rate). I will do my best to try and track down the original data for this series so that a change-from-peak measure can be contructed as again that may be more instructive than a year-on-year change, particularly in six months time.

In the meantime, though, I’ll leave this up here and ask for any insights, comments or queries, as per usual! Fire away…

Filed under: 3 Property Market | Tagged: 3 Property Market, australia, canada, case shiller, cavan, cork, denmark, donegal, dublin, economist, esri, esri house price index, france, galway, germany, hong kong, ireland, irish property market, irish-property-prices, italy, japan, leitrim, limerick, manyeyes, mayo, munster, netherlands, new zealand, property, property-prices, singapore, sligo, south africa, spain, sweden, switerland, tipperary, uk property, uk property market, us property, waterford, westmeath, wexford | 1 Comment »