Last week, there was a brief discussion on thepropertypin of an interesting piece of economic history – in the 60 years following their construction in the late 1780s and early 1790s, the Georgian houses of Mountjoy Square fell in value by almost 94%. By comparison, nominal wages fell about 40%-50% during the same period, while the price of food – if bread is anything to go by – stayed largely the same (8 pence for a loaf of bread in the 1790s and in 1848). While I can’t claim to speak for anyone else reading, I would imagine the general perception was: “So property prices can adjust downward by percentages scarily close to 100% – but it probably takes a unique set of circumstances (Act of Union and all that).”

Yesterday, however, I read on Carpe Diem about the latest property price statistics from Detroit. Houses in Detroit are selling for an average of $11,500 at the moment, down an astonishing 88% from their peak values. That translates into a monthly mortgage payment of $50! And this happened not in 60 years of steady economic decline but in less than five years.

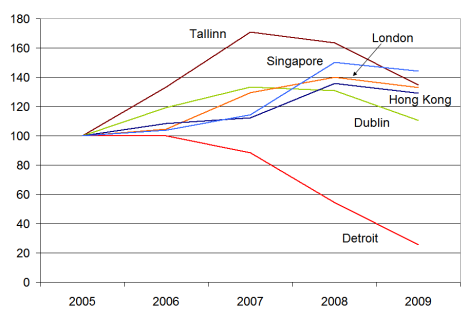

It got me thinking about Ireland’s property market in a global context, so I decided to do a little comparison of 2005-2009 for a smattering of cities. The cities were chosen in no particular way other than to give some global coverage, hence two Asian and one American cities, as well as two Western European and an Eastern European city. The figures refer to the start of the year concerned, with Jan 2005 set at 100 for all cities.

It was a slight surprise to see that, of the cities shown, none apart from Detroit had yet fallen below their Jan 2005 levels by the start of 2009. Indeed, some cities almost 50% above their 2005 levels. Dublin was closest – and more than likely has already fallen back to mid-2004 levels since the start of the year. Tallinn seems to be like an excess version of Dublin – rising and now falling faster. For Singapore and Hong Kong, 2007 seems to have been easily the craziest year, but the correction in 2008 was nowhere near as large. Meanwhile, Detroit props them all up.

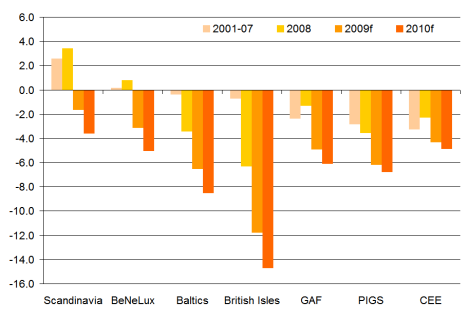

For a view on how much more of a correction is needed for five economies, including the US, Ireland and Spain, you can have a look at property yields over the medium term here.

Filed under: 2 World Economy | Tagged: detroit, dublin, economic history, estonia, hong kong, london, michigan, mountjoy square, property market, recession, singapore, tallinn, thepropertypin, uk, uk property | 1 Comment »